91AV should be welcoming and accessible to everyone. But, all too often, the experiences of disabled chemists and chemistry students are shaped by stigma and discrimination.

There is a pervasive lack of awareness and understanding of disability and accessibility throughout the chemical sciences sector.

Disabled employees often have to self-advocate for the adjustments they need to work comfortably and effectively. But, if organisations and institutions planned environments and processes with inclusion in mind, many barriers would be reduced or eliminated.

NEW: Neurodiversity in the chemical sciences

Explore our new pages to learn more about the strengths and challenges of neurodivergent chemists in the workplace, and access resources.

Embracing disability inclusion is not just a legal or moral obligation. It is a strategic decision that brings numerous benefits to employers, institutions, and society.

We’re here to help the chemical sciences community create a more open, sustainable and equal environment where everyone is welcome.

On this page, we share what we have learnt from those in our community with experience of disability. And we provide suggestions for how organisations and institutions can improve disability inclusion.

On this page

What do we mean by "disabled"?

Disability is a broad term encompassing many conditions, impairments, and differences. These can be mental, physical or both. Disability can be seen or unseen, lifelong or acquired, permanent, temporary or fluctuating.

The umbrella of disability covers:

- sensory and mobility impairments

- neurodivergence

- mental health conditions

- chronic illness

Each disabled person has their own unique experience, influenced by factors such as age, gender, race, ethnicity and culture, socio-economic status, and LGBT+ identity. These factors interact with disability to shape individuals’ experiences and the barriers they face.

Barriers to self-identification

- Many people are unaware that their experience can be described in terms of disablement. For example, a person with a mental health condition or an older person with a physical impairment may not realise the label of disability can apply to them

- Some may not feel comfortable sharing that they are disabled for fear of discrimination

- A proportion may see little benefit of self-identifying

- Others may prefer not to identify with a label that is perceived so negatively by society

- Stigma, imposter syndrome, and a lack of disability awareness are all barriers to self-identifying with a disability

These barriers can prevent disabled people from seeking and getting the support they need to work and study in inclusive, enabling environments. They also highlight the complexity that surrounds the collection of accurate disability data.

Our work aims to foster a science culture that is inclusive and welcoming to all. We encourage positive self-identification with disability and are committed to challenging the stigma. But we also recognise that there will always be a gap between those described by "disability", those who identify with it, and those who choose to share that information. Irrespective of self-identification, our ultimate goal is to make the chemical sciences as accessible as possible for everyone.

How our community recognises their disability

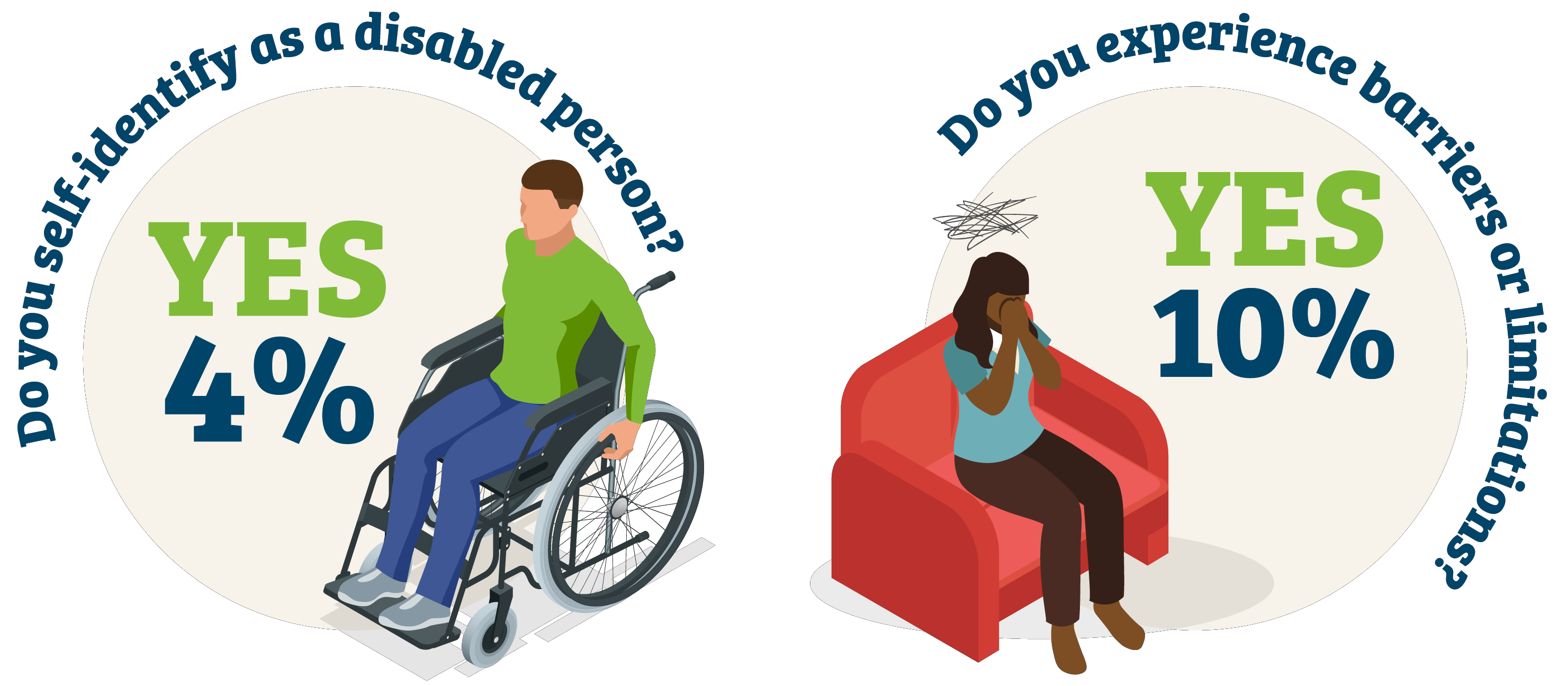

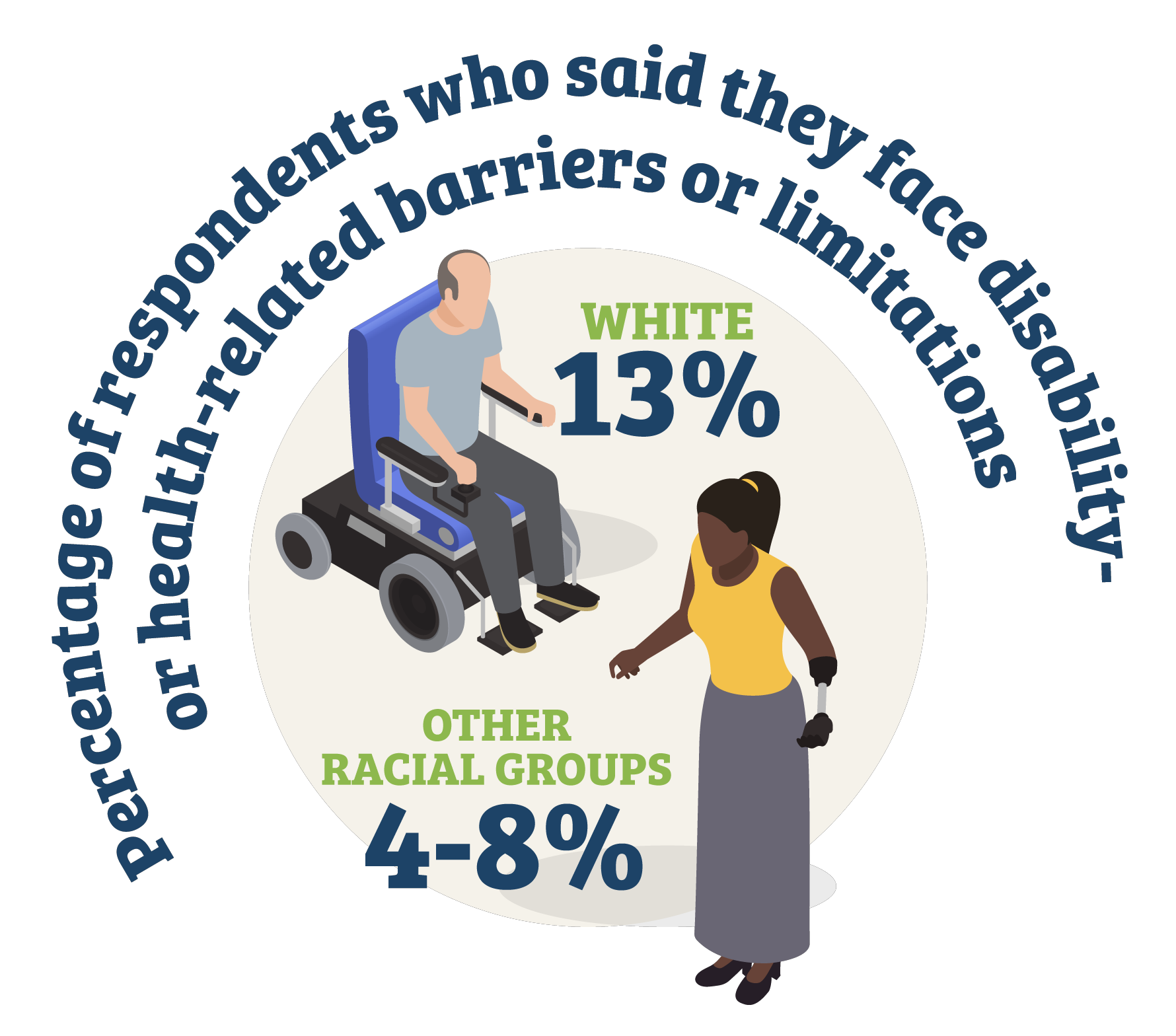

Just 4% of our members self-identify as disabled people. 10% of our members, however, said they "experience barriers or limitations in their day-to-day activities relating to a form of disability, long-term health condition or impairment" - meaning that up to 10% of our members may meet the legal definition of disability.

RSC Member Survey 2022 data

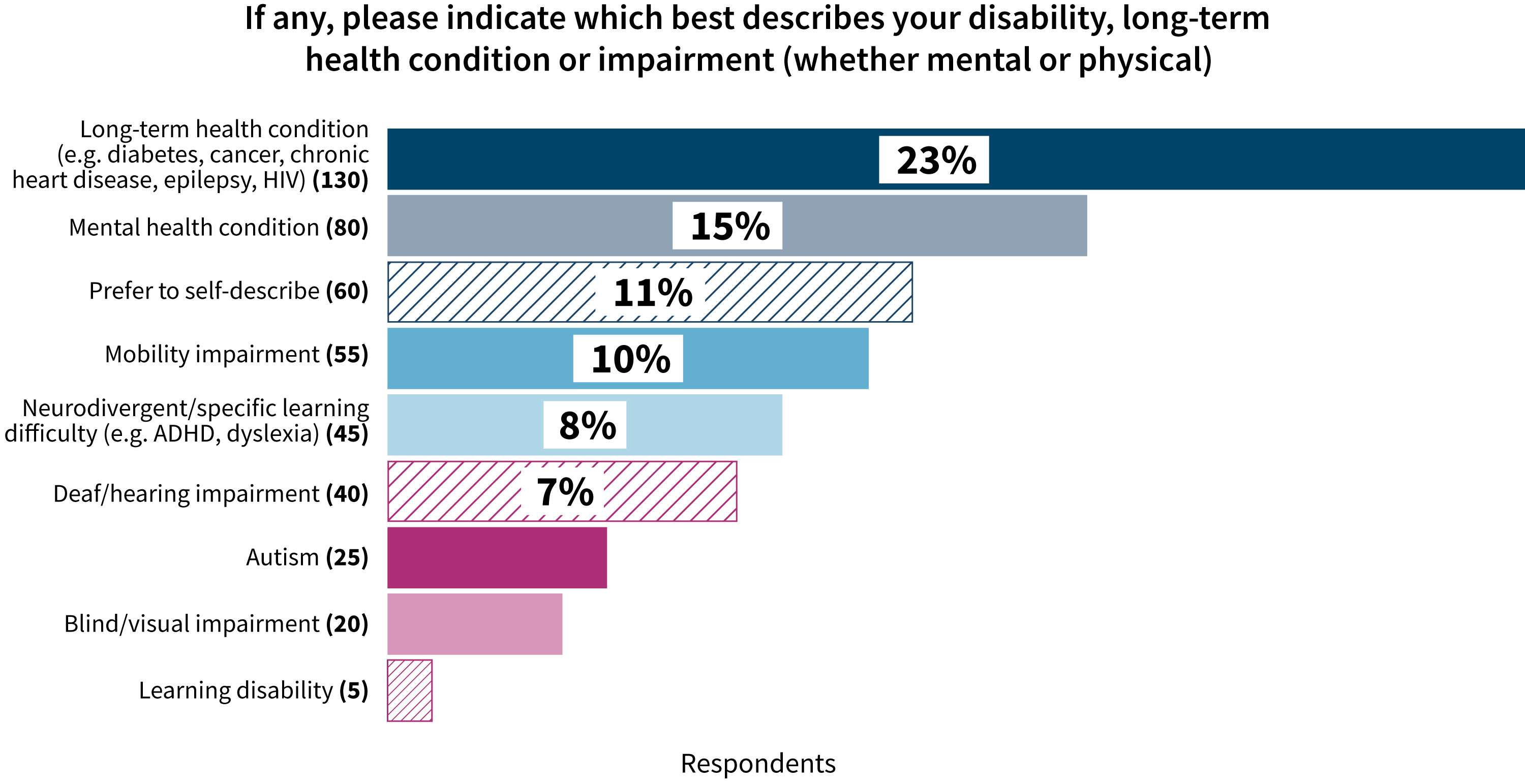

How respondents describe their impairment

Data from 2022 RSC Member Survey, approx 17% of respondents preferred not to say or left blank

Intersectional disabled experiences

Disability intersects with other diversity characteristics in multiple ways, shaping individuals’ experiences and influencing how they navigate society.

The complexity of disability data

Disability data is so complex that it’s hard to draw causal or fundamental conclusions from these trends. It is unclear whether certain groups are more likely to experience disability or are more likely to report their experience of it.

A recurring theme in our focus group discussions was the acknowledgment that access to medical diagnosis and treatment is influenced by race, gender, and sexuality. This underlines the case for moving away from medicalising disability in the workplace and education.

The burden of self-advocacy

Disabled people often encounter situations where they need to advocate for themselves to access a comfortable workplace or study environment. are one example.

This "burden of self-advocacy" can be particularly challenging for those who may already be dealing with the physical, emotional, or cognitive impacts of their disabilities.

The medicalisation of disability

The common requirement for medical evidence – sometimes specialist medical evidence or diagnosis – to access adjustments is a bigger obstacle than non-disabled people realise. It is a generally disproportionate check against system misuse that leaves many disabled people in limbo.

Some of our roundtable participants felt that the requirement for medical evidence represented an unnecessary invasion of their privacy. All agreed it reflected a lack of trust in disabled people’s authority over their experiences. A disabled person is best placed to determine – with professional support if they wish – what would make their working environment more accessible for them.

Medicalising disability disregards the social, cultural, and environmental facets. It reinforces the deficit model, which views the individual’s difference as the problem, not the environment that disables them.

Instead, employers and institutions should empower employees, staff, and students to advocate for the conditions they need to flourish. And the chemical sciences must design workspaces and practices with this human diversity in mind.

Necessary adjustments in the workplace

In the UK and many other countries, . Disability-related support in most workplaces happens primarily on a case-by-case basis. This framework aims to address individuals’ unique needs, but is not without its limitations, as reflected by our research participants.

Administrative and financial hurdles

Some workplace adjustments carry a cost to the employer, like making changes to buildings and providing hardware, software and equipment. But accessing adjustments can also present administrative and even financial hurdles for disabled individuals.

Read moreReliance on specific allies

Some adjustments require ongoing inclusive practice, such as communication support, or flexible working hours.

Read moreInaccessible laboratory spaces

The layout and design of laboratory spaces are often inaccessible for disabled chemists and chemistry students.

Read moreDigital accessibility

Digital accessibility principles often align with good design practices, leading to better user experiences for everyone.

Read moreSupport outside of employment and education

It can be difficult for our disabled community to access support when not in stable employment or a formal education setting.

Read moreCareer progression and job satisfaction

The disparities in pursuing a career in the chemical sciences result in a loss of promising talent from our sector.

Disability and academic career progression

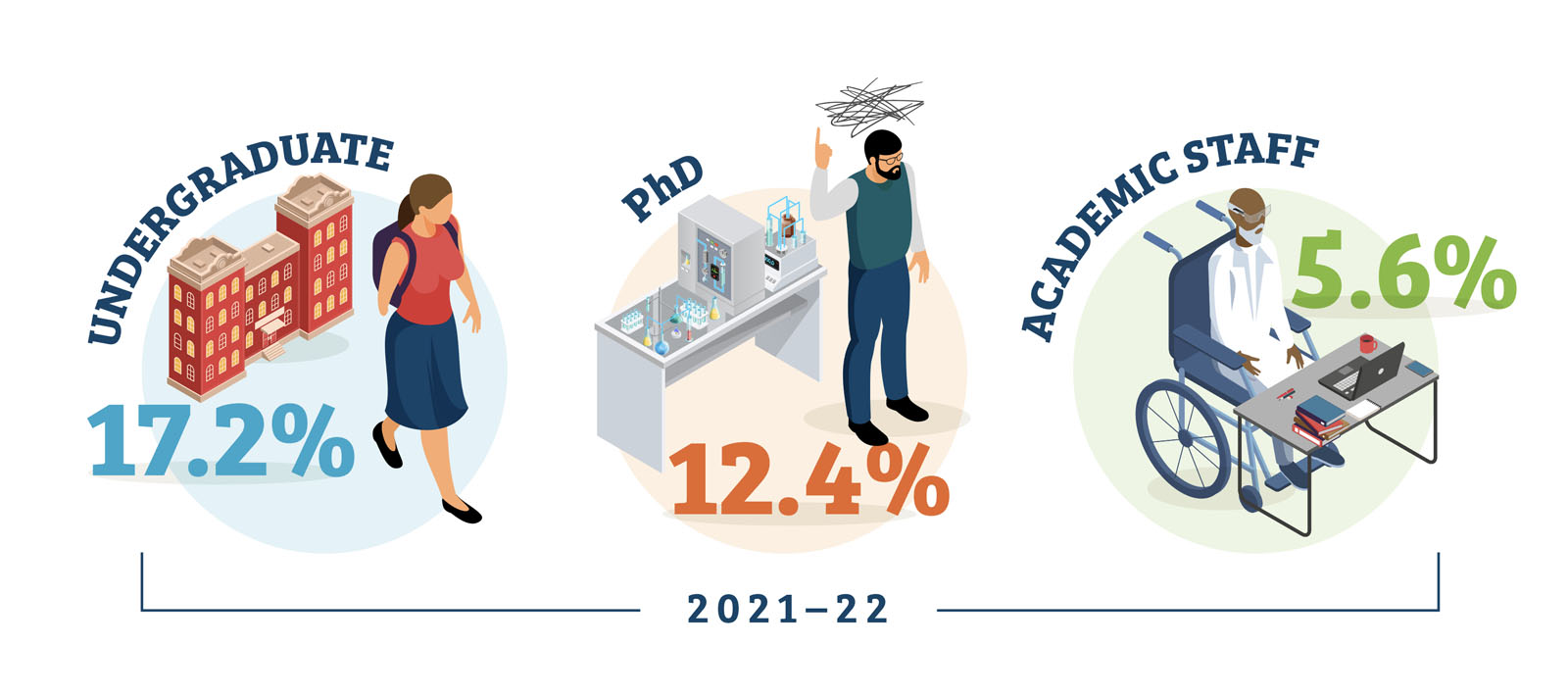

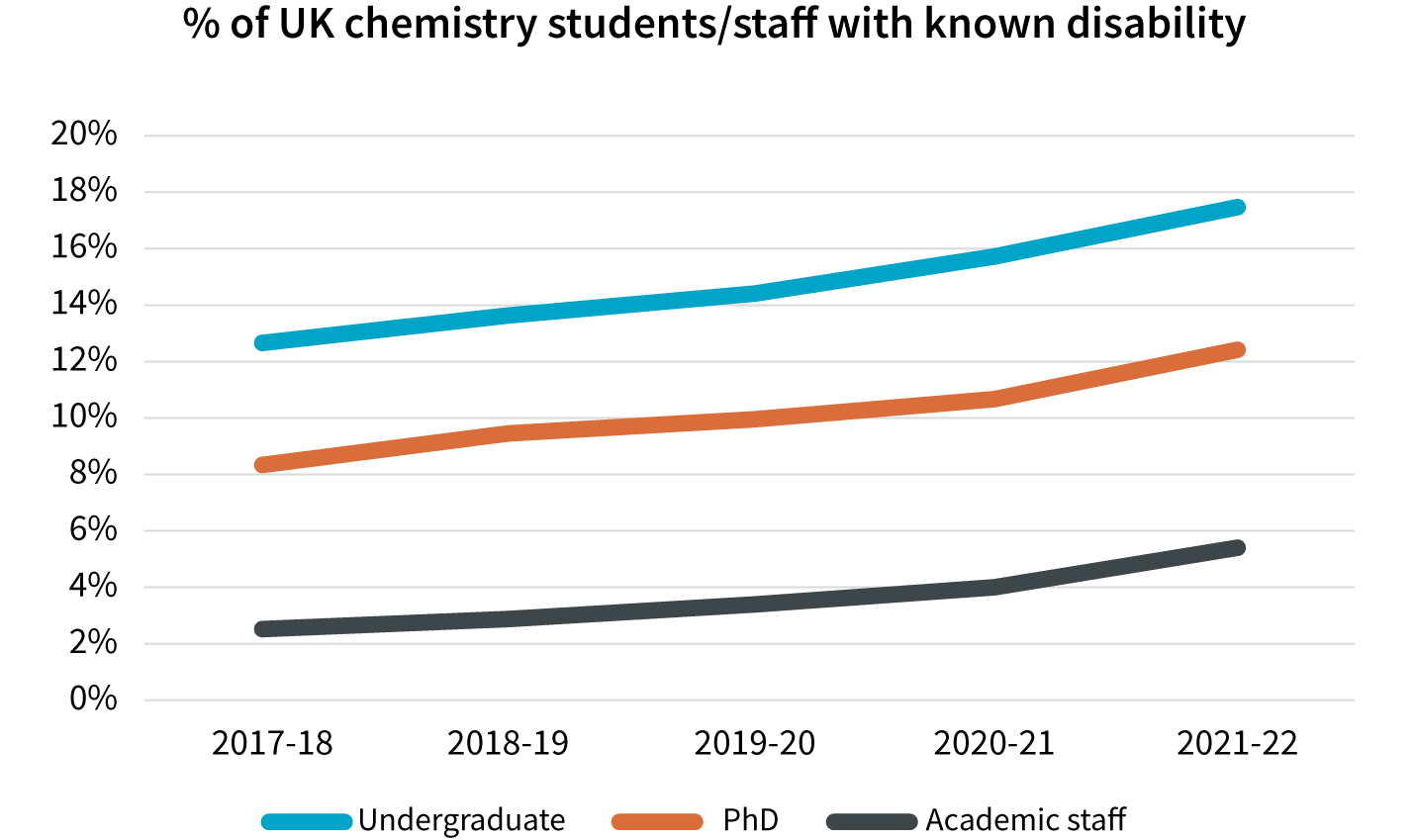

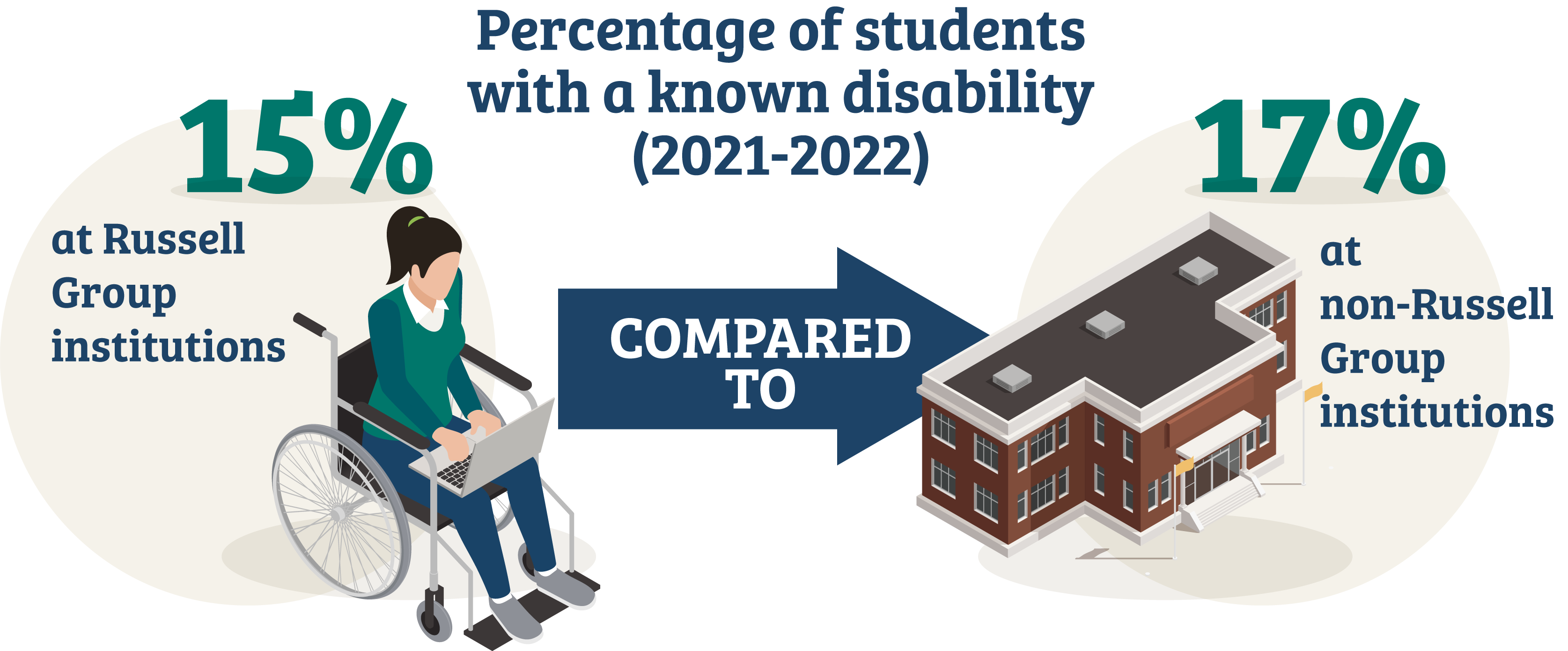

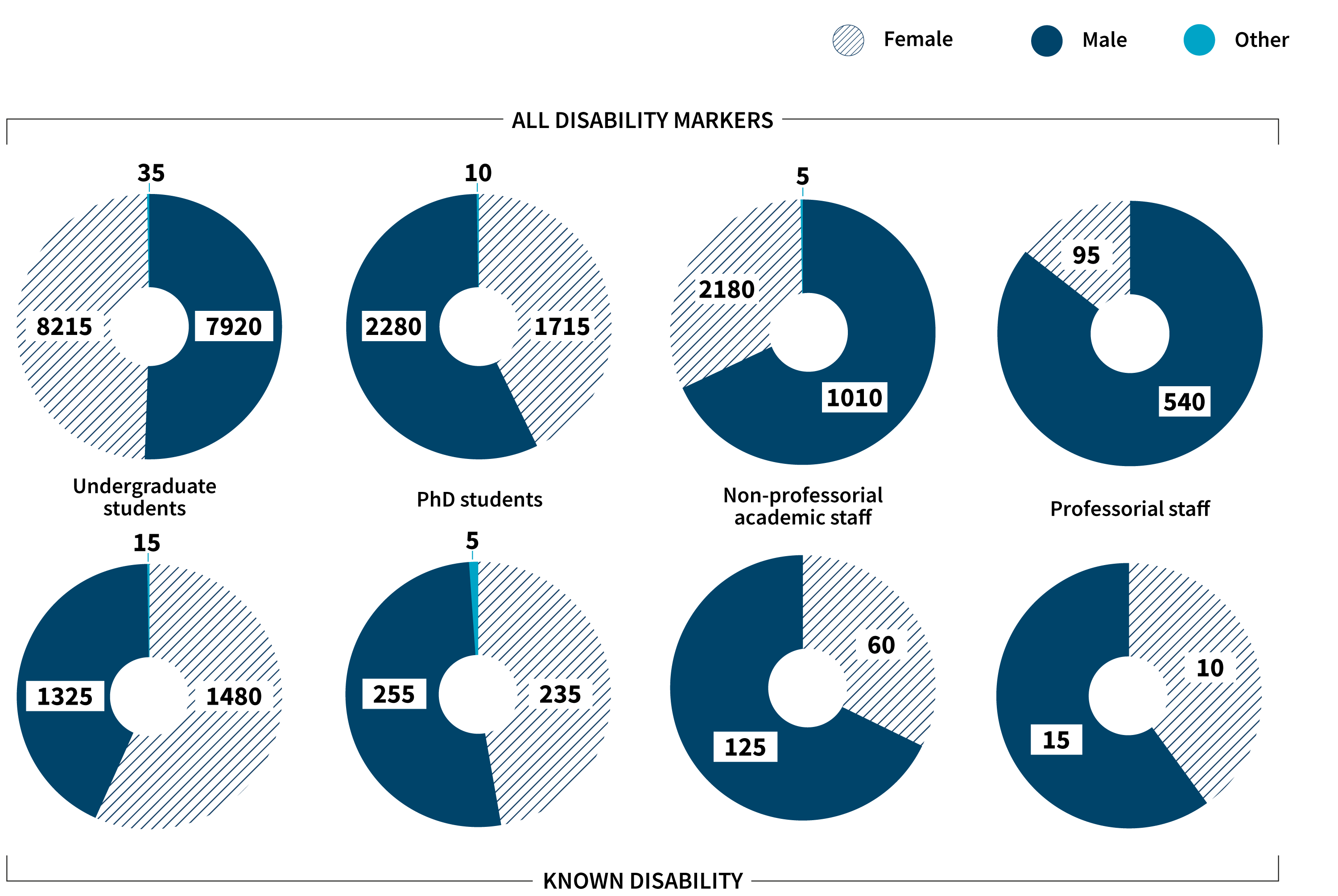

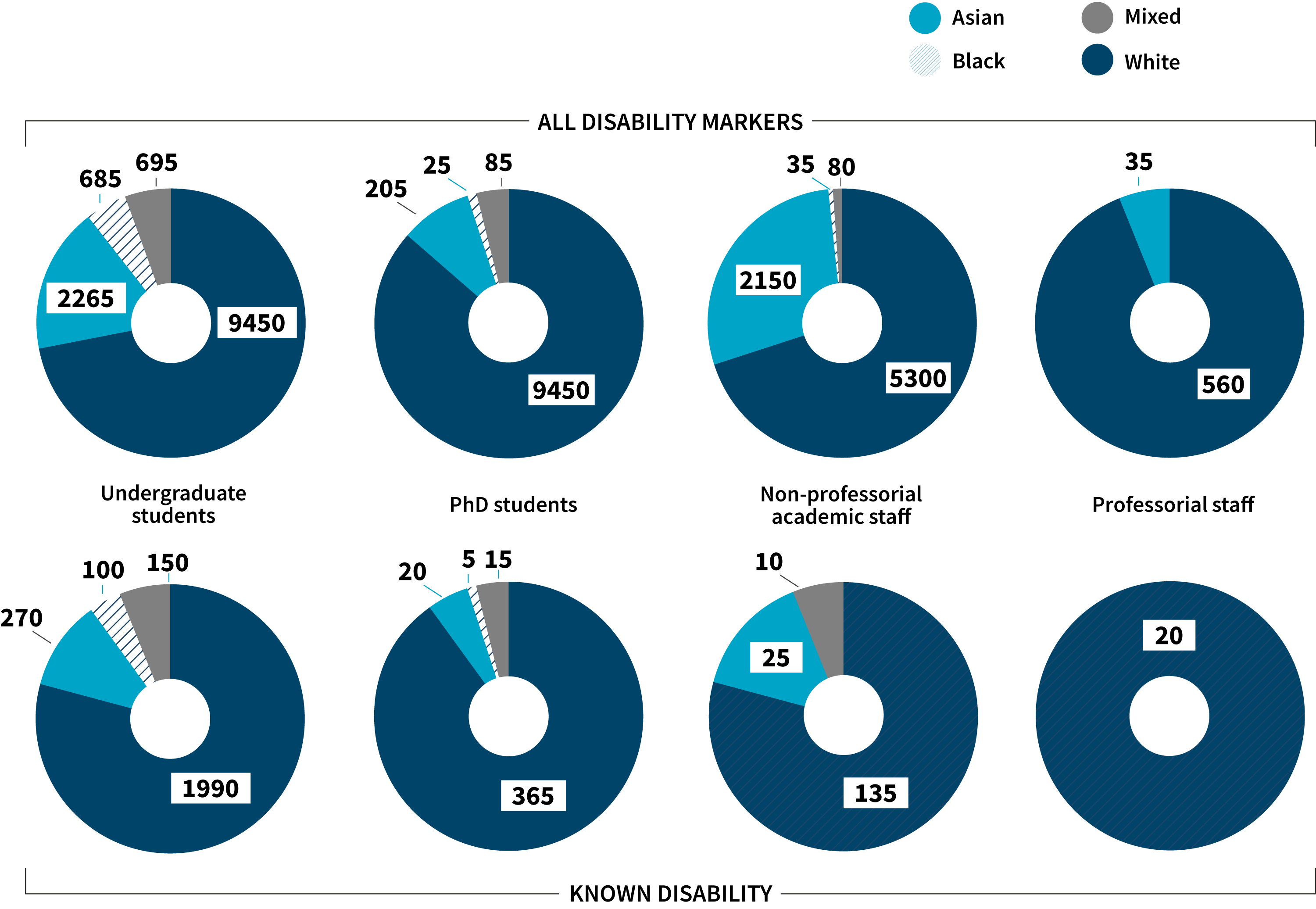

HESA data shows a significant drop-off in disabled chemists at undergraduate and graduate levels who then move into academic employment. In the academic year 2021/2022, only 5.6% of academic staff in chemistry had a known disability, compared to an estimated 23% of the working-age population ().

Read moreIntersectionality in academic career progression

Our analyses of 2021–22 HESA data on disability and gender show a complex picture. A more straightforward 'leaky pipeline' appears for disabled chemists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds.

Read morePay and responsibility

Our Pay and Reward Survey 2021 revealed that disabled chemists are less likely than non-disabled chemists to feel that their pay is fair for the work they do.

Read moreLack of flexible working

Providing flexible working options for disabled workers is a win-win for employees and employers. Allowing employees to work when they are most productive can optimise the performance of an organisation’s workforce.

Read moreAccessing professional development

Networking and professional development environments pose barriers for many disabled chemists.

Read moreThe financial burdens

Living as a disabled person can entail various financial burdens. These can vary depending on the type of care, support or tools needed, and on access to public or job-based funding to support these needs.

The or "disability tax" represents the extra expenses incurred by disabled people to have the same standard of living as a non-disabled person. For example, an individual may need to use wheelchair-accessible taxis, home delivery services, or pay for housekeeping or personal care. Bills may be more expensive for those who need electrical equipment. Healthcare expenses compound these extra living costs, as do reduced earning potential and professional development costs.

The Chemists’ Community Fund provides holistic support to RSC members facing financial difficulties. But funders and employers need to make structural changes to mitigate these barriers. We need a broader review of the structures available to support disabled chemists. For example, a lack of assessors with the necessary scientific expertise compounds long waiting times for financial aid, such as the Disabled Students’ Allowance and Access to Work.

We believe positive targeted action, such as ring-fencing funding for disabled researchers, should be considered. And, sources of funding need to be established to address the barriers we have highlighted, such as the design of accessible laboratories.

Organisational culture and disability awareness

The impact of organisations and institutions on disabled people is multifaceted. Unfortunately, some organisations may perpetuate discrimination or stigmatisation against disabled individuals. This can manifest as bias in hiring decisions and limited opportunities for career progression. Discrimination can also be indirect: if policies and systems are not inclusively designed, they may put disabled people at a specific disadvantage.

Assumptions and a lack of awareness reinforce barriers

The participants in our roundtable shared their personal experiences, highlighting how stigma and discrimination have shaped their lives.

Read moreA lack of commitment to inclusion

Disabled people often become pioneers for change in their organisations simply by pushing for the adjustments they need. Unfortunately, in some cases, they are treated as antagonistic rather than an asset to their organisation.

Read moreAcademic funding structures

Inequalities in academic funding structures disproportionately impact disabled chemists.

Read more

Why we use the social model of disability

According to the social model, ‘disability’ refers to the ways that socially constructed barriers are disabling towards people with impairments or differences. In contrast, the medical model views a person’s disability as arising from their condition or impairment, and sees the individual as someone who needs to be fixed or cured.

The social model highlights the importance of addressing societal structures and attitudes to create an inclusive and accessible environment for everyone. Other, more recently developed models aim to give a more holistic overview of different aspects of disabled experience. From our perspective as a leading voice in the chemical sciences, the social model is most useful for us to design interventions and actions that remove barriers and promote equality for disabled chemists. We link to some of them on this page.

Removing all barriers will be challenging. It requires a collective effort from governments, organisations, communities, and individuals. We can and must continue to improve the accessibility and inclusivity of workplace and study environments. In doing so, we will increase the diversity of people choosing and fulfilling their potential in the chemical sciences.

Useful links: